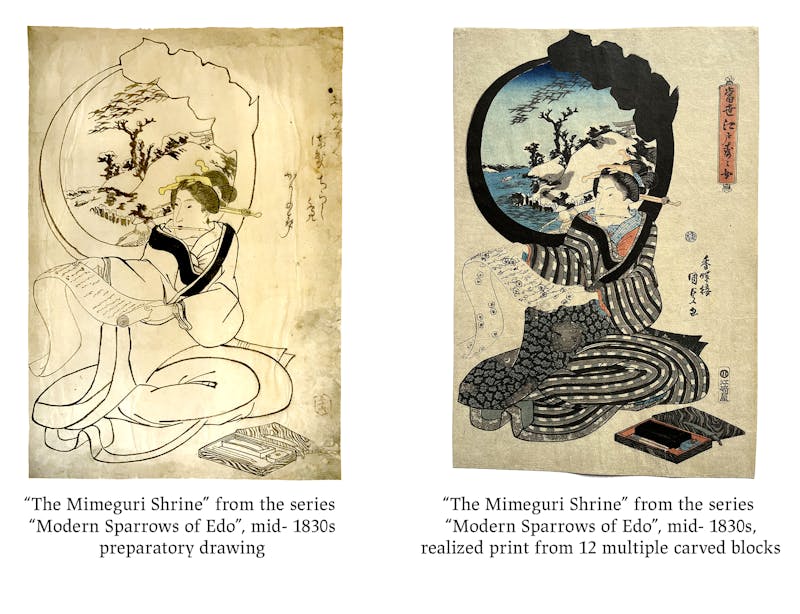

Comparing drawing to print of “The Mimeguri Shrine" from the series “Modern Sparrows of Edo", mid-1830s

Israel Goldman sold me the Kunisada drawing on the left in 2018. Made on a thin paper mounted to another backing paper, it is likely a hanshita, a drawing intended to be pasted face down to a printing block to guide the work of a carver. Because carvers would, following the artist's brush-marks, cut directly through these applied papers, most hanshitas were lost in the production of the prints.

MFA Japanese art curator Sarah Thompson's idea, when I showed her this drawing in 2018, was that this was a sketch proposal never realized as a print.

A facebook posting of the drawing led my fellow Kunisada enthusiast, Taylor McNeil, to reach out and share: he had this print image in his own collection! When you consider that Kunisada's print production is thought to exceed 20,000 images, the coincidence of this connection seems special. This coincidence is the original connection between Taylor and myself. Though we grew up blocks from each other in Washington, DC, we hadn't knowingly met.

Careful comparison of the drawing to the print has offered Taylor and I some conclusions:

1. It seems there was another drawing used as the actual hanshita to make this print.

(Ellis Tinios shows a similar juxtaposition of drawing and print in his 1996 book Mirror of the Stage, The Actor Prints of Kunisada. The reference is in his chapter titled “The Production of Woodblock Prints". Tinios speculates that the hanshita drawings pasted to the blocks were often copied. Tinios postulates that it would be common to have two drawings, as described above.)

2. Kunisada was very, very good with his brush. These days making copies digitally or with a Xerox machine is easy. In Japan in the 1830's? A copy would have to be drawn out, on paper, with a brush. Kunisada's brush control was likely close to super-human. Comparing print images in our exhibition suggests, he could render a ditto copy of a face and figure without aid.

3. The drawing in my collection was likely passed over in favor of another. That other drawing was used as the hanshita for the print in Taylor's collection, for some reason.

What would have been the reason?

Changes in the box holding ink stone and brushes, a shift in the landscape inside the Toshidama porthole, variations in the shorelines, the flock of geese, the trees, the fact the far shoreline of the Sumida river is shifted closer to “level" . . . these are a few of the differences we notice.

Feel you have ideas of your own related to this comparison of drawing and print?

Feel motivated to weigh in on the question?

Send ideas to us at tnlg23@gmail.com. We'll seek to include them on this blog post!

Matt

“Modern Sparrows and the Toshidama" - Taylor McNeil weighs in 1/26/2024:

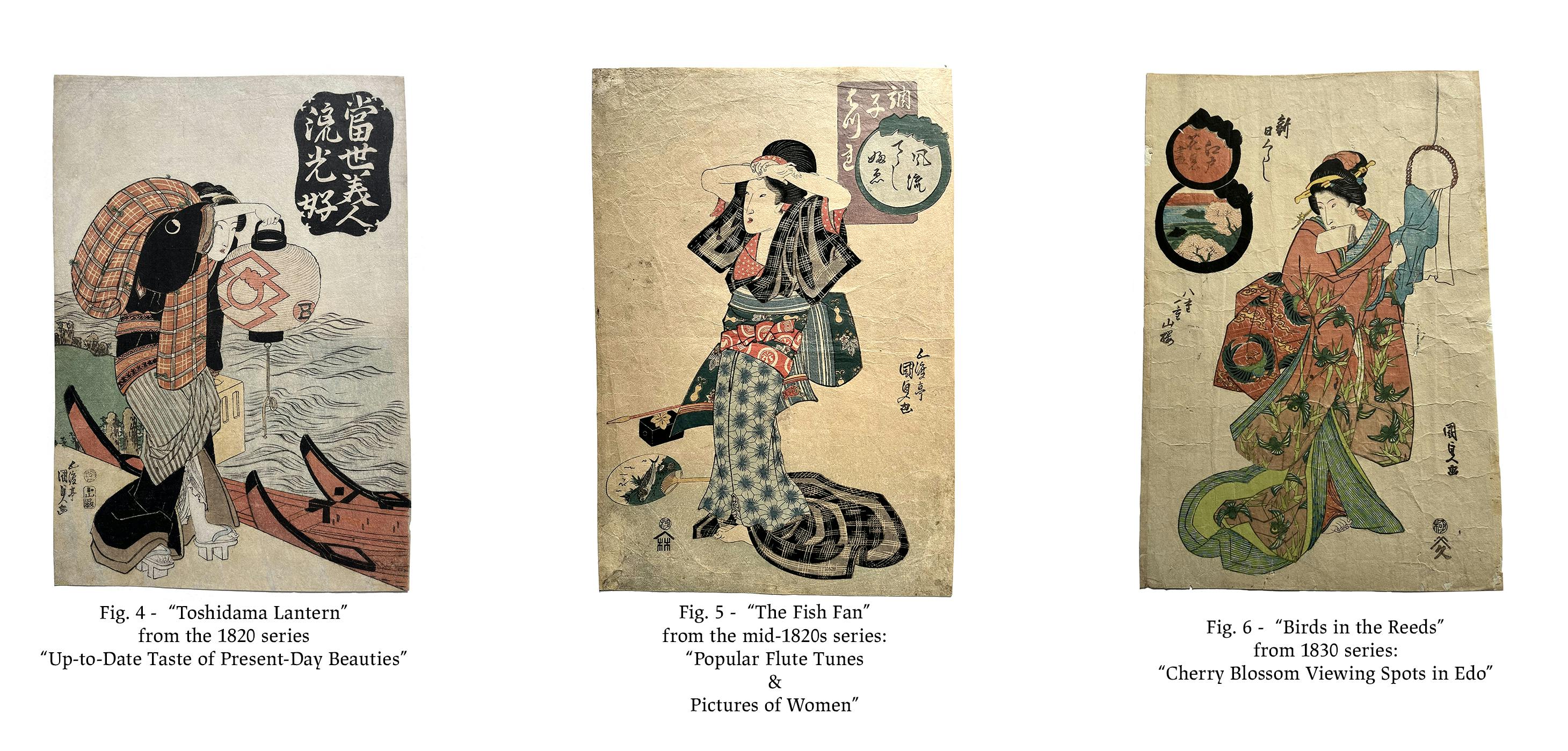

When I first saw “The Mimeguri Shrine" from the series “Modern Sparrows of Edo" (up for auction on eBay in early 2017) I was struck by the signature toshidama seal dominating the print. I’d been collecting an early 1840s series by Kunisada called “One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets,” and on almost all those prints, right underneath the artist’s signature, was a toshidama seal in red, a striking statement that helped unify the series.

What I loved most about “The Mimeguri Shrine" was its bold use of the toshidama seal. Loud and clear it said: I am part of a tradition, the Utagawa School of print designers. The Utagawa School reached its apogee in the 1820s and 1830s, as Kunisada and fellow former students of Utagawa founder Toyokuni I (such as Kuniyoshi and Kuniyasu) dominated the woodblock print scene in Edo.

Note: Artists often used parts of their teacher's names when taking on their artist name. Sadafusa, Sadahide, Sadahiro, Kunimasa, and Kunichika, for instance, were all students of Kunisada, just as Yoshitoshi was a student of Kuniyoshi.

Kunisada used the toshidama seal during his early days as an artist. The print I have from the 1820 series “Up-to-Date Taste of Present-Day Beauties” (fig. 4 above) shows a woman alongside a river carrying a lantern, which has imprinted on it a toshidama seal within a zigzag pattern, while her kimono sports a smaller toshidama seal seal in the cartouche for the series title. Another print, “The Fish Fan" (fig. 5 above) from the mid-1820s series of beauties, “Popular Flute Tunes and Pictures of Women”) features a toshidama seal as the cartouche for the series title. In Kunisada’s 1830 “Cherry Blossom Viewing Spots in Edo” series (fig. 6 on the right above) find a double toshidama cartouche, a stronger statement. The impression included in our exhibit shows a cherry blossom scene from Edo in the larger toshidama below and the series title in the smaller seal above it.

The “Modern Sparrows" series, which includes eight known surviving prints, is the boldest proclamation of Kunisada's affinity with the Toshidama seal. The expressive portal-like windows set scenes (landscapes and favorite spots in Edo) for each of the prints in the series and dominate each of the eight prints. This striking toshidama seal must have resonated with print viewers in 1830s Edo—they likely enjoyed the Toshidama connection with the New Year’s treats. For Edo print buyers, the treat they got was the beauty of the art—the same as it is for us.

“Tools of the Creative Work" - Matt Brown weighs in 2/15/2024:

Brush held between her teeth, painted scroll falling from her hands, ink stone and drawing box laid out below the moving patterns of her kimono, facial features closely juxtaposed with the appealing landscape of the Sumida River beside the Mimeguri Shrine, Kunisada emphasizes dynamics and subtle action in his portrayal of this beauty. Looking at the image we take in the swoops and curves of the figure and the seal, the textured fabric, the presented scroll, and in our imaginations assemble sensations of the world of Edo Japan which made this image.

The toshidama landscape presented alongside this depiction of art getting made? Its as if the art-making envelopes its depicted world, yielding a porthole for us, an image resonant of the depicted porthole inside that toshidama seal.

“Traveling to the World of Edo Japan" - Prof. Ming Meng weighs in, 2/19/2024:

Imagine traveling to another world in another era, such as Edo-era Japan?

Finding cues for travel in a piece of fine art can be a joy similar to finding the right place for a puzzle piece in a jigsaw game: when we understand relationships between elements of works of art, we can get a glimpse into the world in which an artist lived and worked.

Recently, through the construction and multi-perspective presentation of real-world models, OpenAI's Sora achieved a significant breakthrough in generating highly realistic videos. Because our world adheres to fundamental physical laws of force, acceleration, and energy changes, the world model of every individual is interconnected. Sora works by assembling dynamic scenarios out of this physical phenomena we all experience and share. The MBFA Kunisada: Art within Art show leverages this same approach, facilitating a multi-angle, deeper-level model of Japan during the Edo-era by juxtaposing imagery created in that era. With these prints we can intimately experience the charming characters, clothing patterns, color relationships, and symbols that capture aspects of the customs, scenes, and visual communications of that era. We can use our imaginations to re-create and travel to that world, like Sora, by placing puzzle pieces that interconnect.

I visited the juxtaposition of drawing and print at the MBFA gallery in Lyme and felt I could construct a model of the world of the maker of these pieces, through my imagination. Juxtaposing the drawn-line sketch with the full color print full of pattern, realized text, and strengthened relationships of darks and lights, comparing these two gave me the sensation I could assemble puzzle pieces and travel to Edo-era Japan. From the artwork in front of me, I felt I could build a mental model of the spiritual world of the maker of these artworks. When Matt explained the artist lived near the river depicted in the print, that this artist earned a salary through an inherited ferry operating across its breadth, these understandings provided additional perspectives and a feeling of understanding of the world of Kunisada's Edo Japan.

“The Role of Drawings in the Production of Japanese Prints" - Horst Graebner weighs in, 2/25/2024:

Some 50 years ago, before the time of computers, I worked in an advertising agency. I suspect the workflow we followed was similar to the production of the Japanese woodblock prints: one or more sketch were drawn (image and text), these drafts were checked, one drawing was chosen by the customer, then the artists developed the final artwork. This development of the artwork guiding the production always followed this pattern of process.

In the case of the ukiyo-e print, the “final drawing” was given to the carver, the carver would paste the final drawing to the wooden block, carve the block, then make test prints in black and white and return these to the artist for color information for the color blocks. The color blocks were carved similarly to the original line block: carvers followed hand-colored prints pasted face-down to the color blocks. Following carving the print then went into production. I guess a first printing was commonly in the quantity of 200 to 250 copies.

In this process the “final drawing” was destroyed. I feel sure there was usually only one copy of the final drawing; that effort required for a second copy was not unnecessary. A few of Kunisada’s “final drawings” have survived. One example is depicted in Laura J. Mueller’s Competition and Collaboration: Japanese Prints of the Utagawa School (Brill, 2007, page 25). On one margin it contains his message to the publisher and on the other margin a message to the carver. (image 06 and 07) The reason why it was not printed is unknown. A whole series of Kunisada designs can be found in the Nagoya City Museum in Japan. This series shows the inner life of the prostitutes in the brothel. It is very likely that these prints fell victim to censorship and were never printed. These drawings have been published in a book (I can’t read the title because it’s written in “current script” of the time). (image 08)

I personally own a number of drawings that were sold as Kunisada drawings. They are drawn on very thin Japanese paper and are likely from the period. I bought them because I knew the prints they helped create and was convinced that they were drawn by Kunisada. 20 years later, with more knowledge, I have compared these drawings in detail with the prints and have concluded that my drawings are likely not by Kunisada. The details, especially in the faces, deviate too much from Kunisada’s style upon closer inspection. I believe now they were created in Kunisada’s studio as practice work by his students. This is not to say that all Kunisada “designs” that exist are not by Kunisada. I can only say that for sure about the ones that I own.

The drawing here of the Mimeguri Shrine looks very similar to the later print, but the resolution of the images is too low to tell with any greater certainty.

Little note by Matt:

Horst Graebner, who lives in Germany, is the creator and manager of The Kunisada Project, currently the world's most comprehensive catalogue of Kunisada's print production (currently the site shows over 4,000 print designs). On the site's home page Horst describes briefly the history of his effort and the history of Kunisada scholarship. Taylor and I are hugely indebted to Horst for the identification of many Kunisada prints, both from his site and, through communications by email, his deep knowledge of Kunisada's prints.

Matt quotes from Alex Faulkner, owner and director of the Toshidama Gallery in Somerset, England, 2/20/2024:

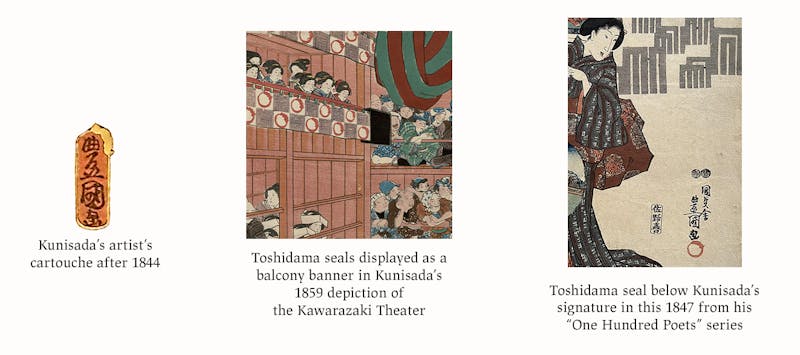

Alex writes of the Toshidama seal:

“The toshidama is an emblem of good fortune. It first appears in around 1808 in the work of Toyokuni I, the founder of the Utagawa School."

Alex goes on to describe the toshidama is an image worked out from a depiction of a coiled cloth enfolding four coins or treats. Kunisada's own artist's cartouche, adopted when he took on the name Toyokuni III in the mid-1840's, is an adaptation of the Toshidama seal. To make the cartouche, Kunisada elongated the round porthole into a tall vertical “plaque". (see illustration below)